The first-ever published research on Tinshemet Cave reveals that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens in the mid-Middle Paleolithic Levant not only coexisted but actively interacted, sharing technology, lifestyles, and burial customs. These interactions fostered cultural exchange, social complexity, and behavioural innovations, such as formal burial practices and the symbolic use of ochre for decoration. The findings suggest that human connections, rather than isolation, were key drivers of technological and cultural advancements, highlighting the Levant as a crucial crossroads in early human history.

A new discovery at Tinshemet Cave in central Israel is reshaping our understanding of human interactions during the Middle Palaeolithic (MP) period in the Near East. The cave, remarkable for its wealth of archaeological and anthropological findings, has revealed several human burials—the first mid-MP burials unearthed in over fifty years.

This research, published in Nature Human Behaviour, marks the first publication on Tinshemet Cave and presents compelling evidence that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens in the region not only coexisted but also shared aspects of daily life, technology, and burial customs. These findings underscore the complexity of their interactions and hint at a more intertwined relationship than previously assumed.

The excavation of Tinshemet Cave, led by Professor Yossi Zaidner of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Professor Israel Hershkovitz of Tel Aviv University, and Dr Marion Prévost of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has been ongoing since 2017. A primary goal of the research team is to determine the nature of Homo sapiens–Neanderthal relationships in the mid-Middle Palaeolithic Levant. Were they rivals competing for resources, peaceful neighbours, or even collaborators?

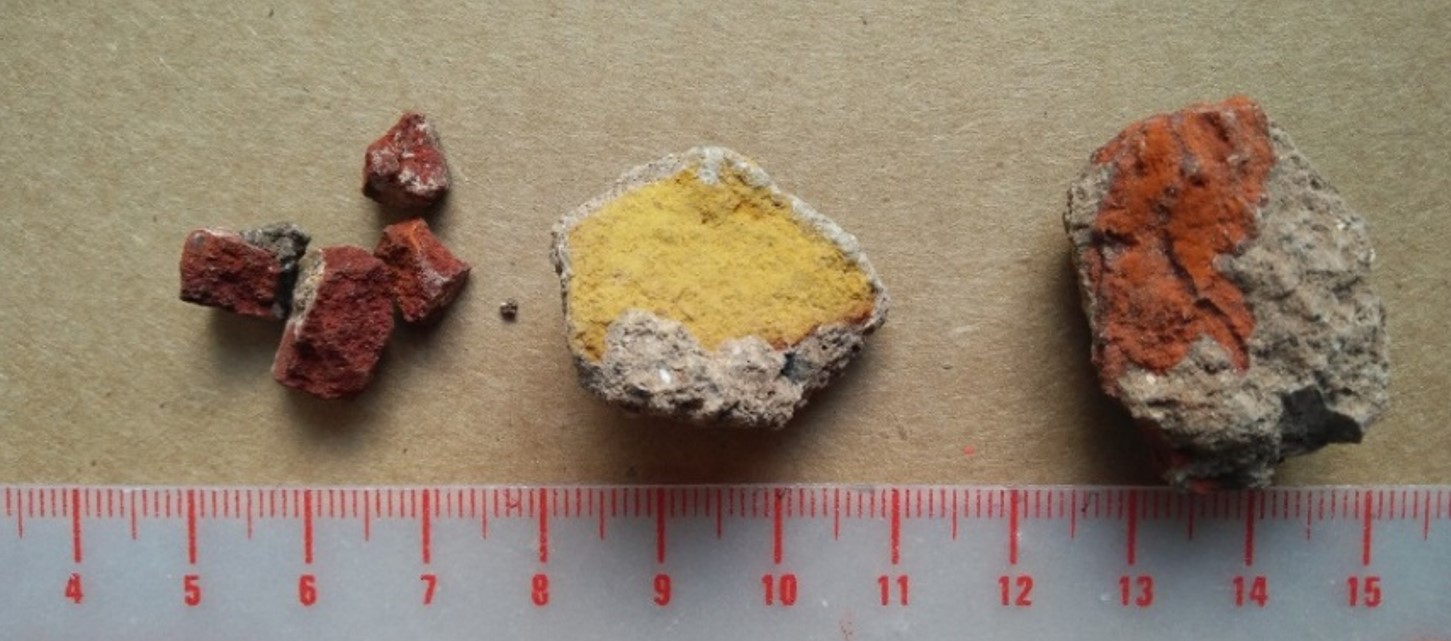

By integrating data from four key fields—stone tool production, hunting strategies, symbolic behaviour, and social complexity—the study argues that different human groups, including Neanderthals, pre-Neanderthals, and Homo sapiens, engaged in meaningful interactions. These exchanges facilitated knowledge transmission and led to the gradual cultural homogenisation of populations. The research suggests that these interactions spurred social complexity and behavioural innovations. For instance, formal burial customs began to appear around 110,000 years ago in Israel for the first time worldwide, likely as a result of intensified social interactions. A striking discovery at Tinshemet Cave is the extensive use of mineral pigments, particularly ochre, which may have been used for body decoration. This practice could have served to define social identities and distinctions among groups.

The clustering of human burials at Tinshemet Cave raises intriguing questions about its role in MP society. Could the site have functioned as a dedicated burial ground or even a cemetery? If so, this would suggest the presence of shared rituals and strong communal bonds. The placement of significant artifacts—such as stone tools, animal bones, and ochre chunks—within the burial pits may further indicate early beliefs in the afterlife.

Prof Zaidner describes Israel as a “melting pot” where different human groups met, interacted, and evolved together. “Our data show that human connections and population interactions have been fundamental in driving cultural and technological innovations throughout history,” he explains.

Dr Prévost highlights the unique geographic position of the region at the crossroads of human dispersals. “During the mid-MP, climatic improvements increased the region’s carrying capacity, leading to demographic expansion and intensified contact between different Homo taxa.”

Prof Hershkovitz adds that the interconnectedness of lifestyles among various human groups in the Levant suggests deep relationships and shared adaptation strategies. “These findings paint a picture of dynamic interactions shaped by both cooperation and competition.”

The discoveries at Tinshemet Cave offer a fascinating glimpse into the social structures, symbolic behaviours, and daily lives of early human groups. They reveal a period of profound demographic and cultural transformations, shedding new light on the complex web of interactions that shaped our ancestors’ world. As excavations continue, Tinshemet Cave promises to provide even deeper insights into the origins of human society.

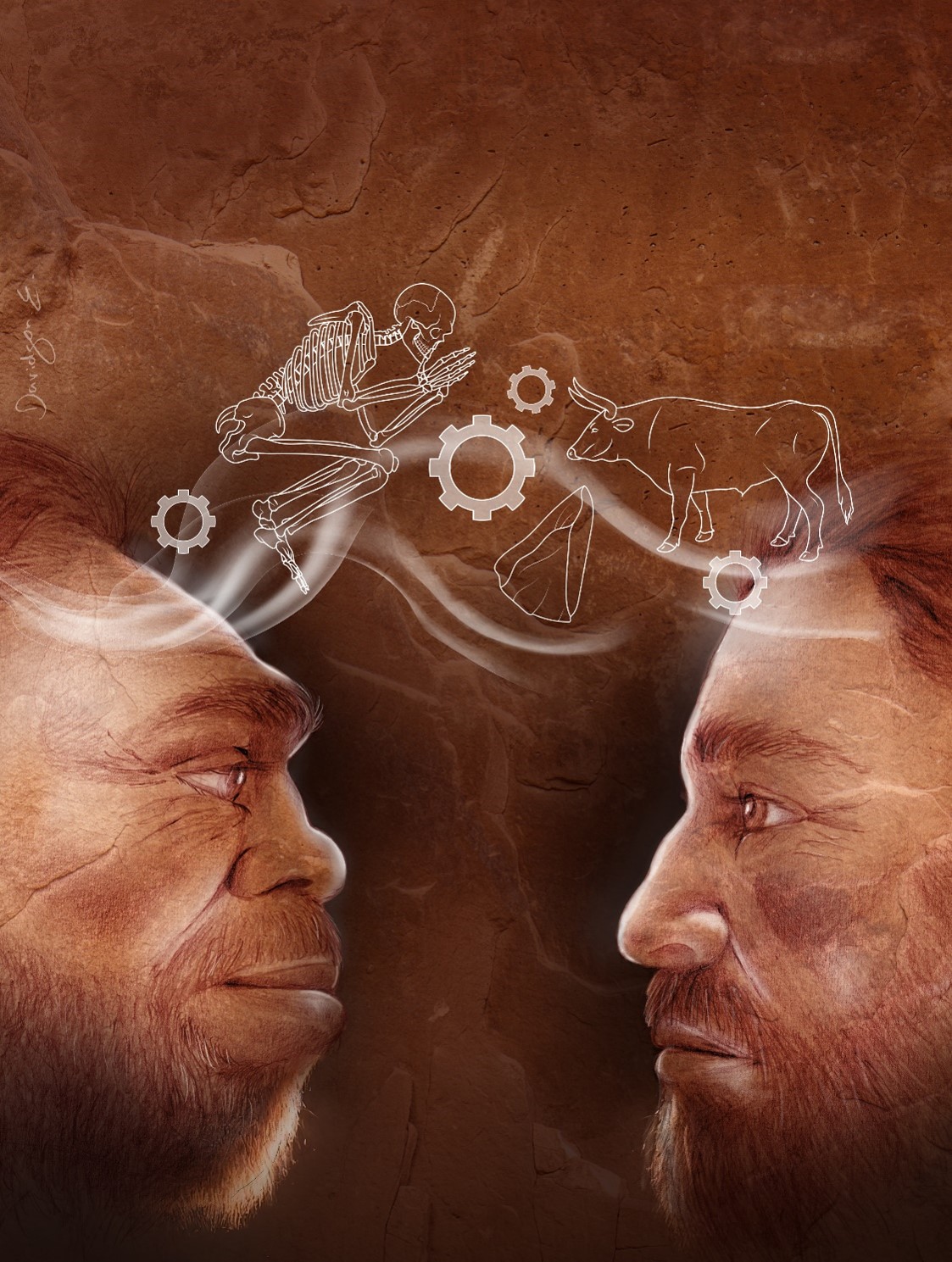

Photo above: Illustration representing Homo sapiens and the Neanderthal sharing technology and behaviour | credit Efrat Bakshitz

Ochre. Tinshemet Cave provide evidence for the extensive use of ochre (mineral pigments), which may have been used for body decoration | credit: Yossi Zaidner

Yossi Zaidner excavating human 110 thousand years old human skull and associated artifacts | credit: Boaz Langford

The research paper titled “Evidence from Tinshemet Cave in Israel suggests behavioural uniformity across Homo groups in the Levantine mid-Middle Palaeolithic circa 130,000–80,000 years ago” is now available in Nature Human Behaviour and can be accessed here.