New study demonstrates that certain incised stone artefacts from the Levantine Middle Palaeolithic, specifically from Manot, Qafzeh, and Quneitra caves, were deliberately engraved with geometric patterns, indicating advanced cognitive and symbolic behaviour among early humans. In contrast, artefacts from Amud Cave, with shallow and unpatterned incisions, are consistent with functional use. This research highlights the intentionality behind the engravings, providing key insights into the development of abstract thinking and the cultural complexity of Middle Palaeolithic societies.

A new study led by Dr Mae Goder-Goldberger (Hebrew University and Ben Gurion University) and Dr João Marreiros (Monrepos Archaeological Research Centre and Museum for Human Behavioural Evolution, LEIZA, and ICArEHB, University of Algarve), in collaboration with Professor Erella Hovers (Hebrew University) and Dr Eduardo Paixão (ICArEHB, University of Algarve), has shed new light on the behavioural complexity of Palaeolithic hominins. Published in [Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences], the research explores the intentionality behind incised stone artefacts, providing compelling evidence of abstract thinking and symbolic behaviour during the Middle Palaeolithic period.

Until now, the intentionality of Middle Palaeolithic incised stone artefacts was broadly accepted and although not well-supported by empirical testing. Many archaeologists viewed these marks as functional, created through tool use or natural wear. There was skepticism about the existence of abstract or symbolic thought in early hominins, with the understanding that symbolic behaviour, such as art or abstract expression, emerged much later in human evolution and is specifically associated with modern humans. This study challenges that view, offering evidence of deliberate, symbolic engravings prior to global colonisation by modern humans.

The study focuses on artefacts from key Levantine sites, including Manot Cave, Amud Cave, Qafzeh Cave, and the open-air site of Quneitra. Using advanced 3D surface analysis, the researchers examined the geometry and patterns of incisions to distinguish intentional engravings from functional marks. The findings reveal striking differences:

Artefacts from Manot, Qafzeh, and Quneitra feature deliberate engravings with geometric patterns that align with the surface topography, underscoring their aesthetic and symbolic intent. In contrast, incisions on artefacts from Amud Cave are shallow, unpatterned, and consistent with functional use as abraders.

Dr Mae Goder-Goldberger explains, “Abstract thinking is a cornerstone of human cognitive evolution. The deliberate engravings found on these artefacts highlight the capacity for symbolic expression and suggest a society with advanced conceptual abilities.”

Dr João Marreiros added, “The methodology we employed not only highlights the intentional nature of these engravings but also provides for the first time a comparative framework for studying similar artefacts, enriching our understanding of Middle Palaeolithic societies.”

While the engraved artefacts from Qafzeh, Quneitra, and Manot are isolated initiatives within their chronological and geographic contexts, the shared traits of the incisions themselves and the similarities in pattern structuring suggest intentional, predetermined actions. These findings deepen our understanding of symbolic behaviour and offer crucial insights into the cognitive and cultural development of early hominins.

This research marks a significant step toward understanding the scope of symbolic behavior of our ancestors, bridging the gap between functional tool use and abstract expression.

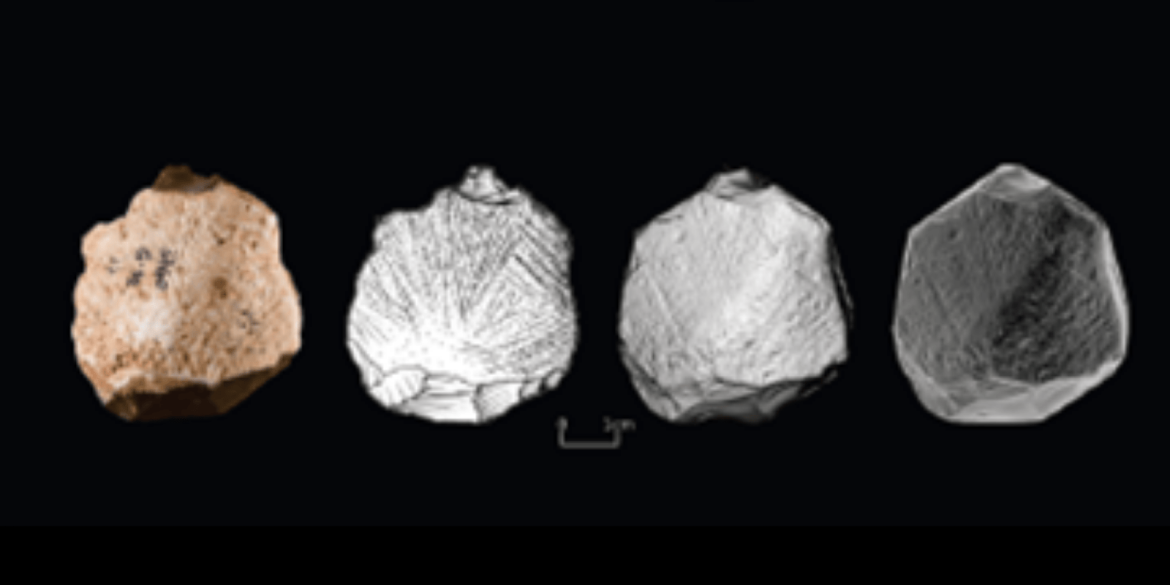

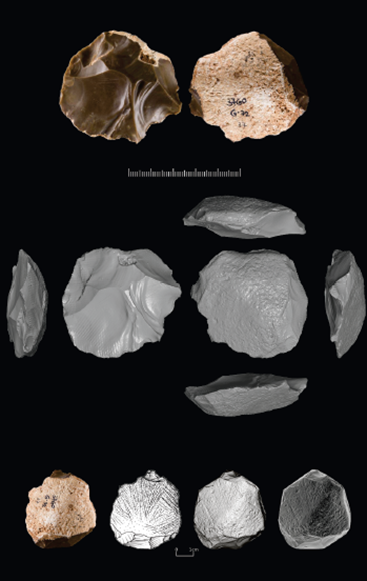

Pictures

The engraved cortical Levallois core of Manot. High-resolution photograph and 3D model (photo by E. Ostrovsky and drawing by M. Smelansky, 3-D models by E. Paixao and L. Schunk.)

Photo of Amud 1, the retouched blade, note the Incisions on the cortex

The research paper titled “Incised stone artefacts from the Levantine Middle Palaeolithic and human behavioural complexity” is now available in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences and can be accessed here doi.org/10.1007/s12520-024-02111-4

For a century, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem has been a beacon for visionary minds who challenge norms and shape the future. Founded by luminaries like Albert Einstein, who entrusted his intellectual legacy to the university, it is dedicated to advancing knowledge, fostering leadership, and promoting diversity. Home to over 23,000 students from 90 countries, the Hebrew University drives much of Israel’s civilian scientific research, with over 11,000 patents and groundbreaking contributions recognised by eight Nobel Prizes, two Turing Awards, and a Fields Medal. Ranked 81st globally by the Shanghai Ranking (2024), it celebrates a century of excellence in research, education, and innovation. To learn more about the university’s academic programs, research, and achievements, visit the official website.